What’s New

Stories

Komatsu-ben: The Dialect of Komatsu

Komatsu-ben: The Dialect of Komatsu

Dialects of the Japanese language are a fascinating story. Although not as well known for its dialectal diversity as languages such as Spanish or English, the Japanese language also takes drastically different forms as you travel from region to region. Japan is a big country after all, however; this is not necessarily why. Russia, the biggest country in the world, actually sees pretty minimal dialectal variation in its national language (Russian) compared to other European languages and Slovenia, for example, sees a massive diversity of dialects. Why? Well, that’s a complex question, but many attribute this to Slovenia’s mountainous geography which isolated regions from others throughout history and thus fostered dialects of the Slovene language to diverge largely.

Now let’s take a look at Japan.

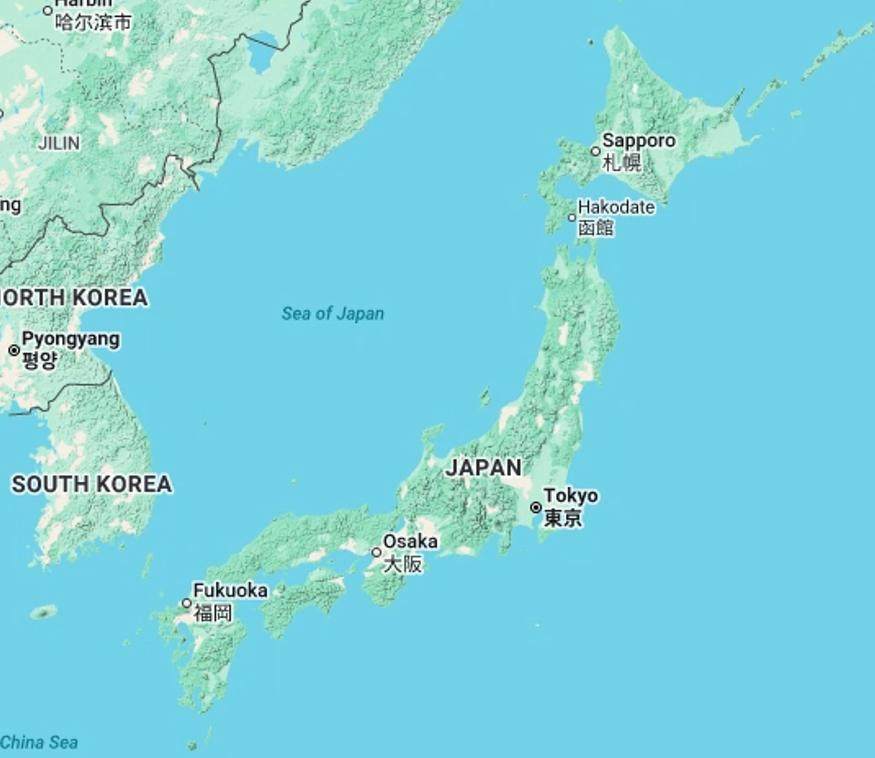

A large mountainous archipelago country with over 6000 islands and tall mountains and deeply forested areas…

It’s fair to say you can see how Japan may have particularly strong regional identities. To add to this, the Edo period was a time in which Japan was extremely isolated and travel between regions was limited. This caused small language-ecosystems in which ways of speaking evolved without contact with other fiefs and as a result, new linguistic elements emerged that did not necessarily exist in neighboring regions, simply because people were not communicating as much across borders and thus these elements cannot disperse as easily.

Add all this together and you are left with a collage of dialects of one language that at their most extreme, can be as little as only 14% mutually intelligible to the standard Tokyo variety, such as in rural villages in Nagano prefecture.

As with many languages around the world, dialectal variation is sadly in decline. With the advent of modern technology, communicating across long distances is now instant and Japanese people are exposed to significantly greater amounts of Japanese from other regions through social media. As a result, this leads to influence from dominant dialects (namely, Tokyo) infiltrating the minds of all Japanese speakers; thus, young people begin to use language akin to what they hear in media and less and less the language they may hear their grandparents speaking, for example.

To put this into perspective, in recent decades you may find speakers of English from the UK or Australia increasingly likely to use vocabulary from American English as speakers from these countries are so heavily exposed to American English. This, bit by bit, leads to a convergence of dialects. Japan, with a geographical range much smaller than the entire English-speaking world, sees this even more severely, leading to the emergence of a generation that speaks an ever more neutral dialect of Japanese and sadly elements of dialectal variations of Japanese being lost to history.

There is hope, however…

Language is seen by many as more than a communication tool but an expression of cultural identity and many, including young people, enjoy preserving their region’s way of speaking as a symbol of regional identity, even though they may be completely capable of understanding standard Tokyo variety of Japanese.

Zooming into Hokuriku, there exist a subgroup of Japanese dialects that color the beautiful landscape of the Hokuriku region. The dialects of Hokuriku carry substantial influence from the Kansai area due to the deep cultural relationship the two regions have. Looking even closer, Komatsu was part of the Kaga Domain and thus its dialect of Japanese is often known as Kaga-ben (Kaga dialect), the same can be said for Kanazawa-ben. Note: the suffix “-ben” 「―弁」means “dialect”.

Let’s look at some specific instances of Komatsu-ben (Komatsu dialect):

小松の森は小松駅の近くやと思う

(Komatsu-no-mori is close to Komatsu Station, I think)

Have you ever heard locals from Osaka say 「そうやなー」? (そうだね). This is also extremely common in Komatsu with the particle 「ね」becoming 「な」 and 「や」 used in place of the copula da. (You may also hear 「じゃ」 being used in this form too)

小松シェアサイクルでハニベ巌窟院(がんくついん)まだしも、那谷(なた)寺(でら)なんて行けん

(I couldn’t even go to Hanibe Hell Caves by ShareCycle, let alone places as far as Natadera!)

The ending of negative verbs in Komatsu dialect often manifests as the 「―ない」 ending contracting to 「-ん」(as in 「行けん」 instead of 「行けない」). This phrase here indicates that the speaker feels that they couldn’t even cycle to Hanibe Hell Caves by sharecycle, let alone going somewhere as far away as Natadera! It’s pretty far to be fair… but you could definitely do it.

安宅関(あたかのせき)の日の入りを見に行きまっし

(Go and watch the sunset over Ataka Barrier Ruins!)

Potentially the most famous of all is the「-まっし」 suffix. It can generally be equated to 「―なさい」 or 「-て行きませんか」 as a soft command. You may have heard this in promotional materials for Kanazawa tourism in the form of 「金沢来まっし」. This one is iconic for Ishikawa dialects of Japanese. In this case, the speaker is suggesting that the listener should go to Ataka Barrier Ruins to watch the sunset. I am the speaker; you are the listener; you definitely need to see the beautiful sunset there.

木場潟(きばがた)でできる水上競技(すいじょうきょうぎ)は、えっぺあるよ!

(There are loads of different watersports you can do at Lake Kibagata!)

「えっぺ」 is roughly the same as 「たくさん」 and it means “a lot”. It’s true, there’s a lot to do at Kibagata!

50年間小松に住んどったのに、小松のトマトカレー食べたことなんって。じょんながや

(Despite living in Komatsu for 50 years, she hasn’t tried Komatsu curry. It’s strange, isn’t it)

A fun phrase to use with Komatsu locals, 「じょんながや」 is roughly the equivalent to 「面白いよね」. If you can master this one, you’ll be presumed a native! Careful though, it carries more of a negative connotation and can be translated as something along the lines of “weird” or “strange”. I can indeed testify that not trying the delicious Komatsu curry after so long in Komatsu would be crazy.

Some additional grammar for fellow language nerds:

– In Komatsu’s dialect, the particle 「ね」 often becomes 「な」

十二ヶ滝の雰囲気が穏やかやな The ambience of Junigataki Falls is so peaceful, isn’t it?

– The word 「そう] (like that) often becomes 「ほう」

小松空港の香港便が再開されたのは便利やな!ほうやな。It is so convenient that they’ve resumed the flight to Hong Kong from Komatsu airport! It is, isn’t it!

– The verb to be for animate objects, 「いる」 you will often hear as 「おる」

最近熊がえっぺおるって言われとるのに、荒俣狭に行くことにした Even though they’re saying there are a lot of bears, we decided to go to Aramata Gorge.

– The question particle 「か」 often becomes 「け」 or 「っけ」

今週末サイエンスヒルズコマツに行かんけ?Do you wanna go to Science Hills this weekend?

– The 「―んだ」 grammar that is used to indicate a context cue often transforms to 「ねん」 or 「げん」 in Komatsu.

もう苔の里にも行ったことあるげんて He said he’s already been to Hiyo Moss Village

Have you ever heard Komatsu locals using any of these?

Note, however, that the existence of a phrase does not necessarily mean all Komatsu locals will use or even understand it. Additionally, dialect is often reserved for less formal situations so don’t try to use these phrases at work. Additionally, regardless of language, it’s common practice to subconsciously use more neutral language around non-locals or non-native speakers. This is because in special circumstances, elements of the dialects can be specific to individual villages. Try to keep your ears open for hearing parts of Japanese in Komatsu that sound different, maybe even try and reproduce this when you speak! If you really want to make an impact and use Line, you can even buy sticker packs that use Komatsu-ben.